Disclaimer: This post talks about race and racial issues and might make some readers uncomfortable. If you have fixed ideas about race and class that you don’t like to have challenged you may want to click away now. Also, the amount of historical research involved was minimal- not much more than looking up a date or two and finding a couple of maps. The rest of this post was written entirely from memory and local knowledge. So if we’re slightly off on something or have omitted a fact here or there try not to dwell on it. Our intention is to write a blog post and not a book, and we believe this post is accurate enough to get at the spirit of what we mean to say. Feature image is Baltimore as it appeared in the mid-1700’s and came to us through mesda.org.

Recently we were lucky enough to be in attendance for a panel discussion at Red Emma’s, the topic of which was Looking Back, Thinking Forward: Organizing to Breach Baltimore’s Racial Divide. It’s always a pleasure and a privilege to be in the same room and get to listen to some of the city’s brightest and most progressive thinkers. While the voices of people like Marc Steiner and Paul Coates are inspiring and encouraging, there was something about the panel’s words last week that left us with a heavy heart as well. We think it’s fair to say that the entire panel and virtually all of the audience would agree that when it comes to organizing urban neighborhoods we can identify some of our major problems, but solutions are debatable at best and mysterious at worst. With development and displacement increasingly in the news in Baltimore these issues are beginning to feel increasingly urgent.

Today we’d like to touch on a problem of neighborhood organizing that was not discussed last week. It’s a nationwide problem, but is as acute in Baltimore as it is anywhere. A large part or the problem facing would-be organizers, neighborhood groups, civic boosters and the rest is this: people are becoming completely disconnected from their neighborhoods. Lifelong loyalties are almost entirely a thing of the past.

Last Friday the Baltimore Sun’s website published an eye-rollingly insipid quiz asking ‘Which Baltimore Neighborhood Should You Call Home?’ While not explicitly offensive, many Twitter users (including the Chop) found this quiz to be in extremely poor taste. There are a number of things we find troubling in the quiz itself, not the least of which is the editorial decision-making process behind it. Someone was assigned (or at least allowed) to spend time and resources in writing it and coming up with the scoring mechanism, and it was published around lunch hour on a Friday in order to attract the attention of bored office workers and insure maximum shareability via social media.

But what troubles us the most isn’t that, it’s the dog-whistle nature of the question itself. This quiz was produced for a very specific type of person: Mid-twenties, college graduate, not from here, working downtown, no kids, and possessed of ‘good taste’ in food, drink and pop-culture. It’s for Yuppies.

But let’s take a step back here. Let’s put aside yuppies. Let’s also put aside those folks in public housing or the lowest-rent neighborhoods who have virtually no choice in where to move. Let’s talk about what makes working class and middle class Baltimoreans choose the neighborhoods they do. In order to do this we’ve got to go back a bit further than you might think. In order to really understand the matter we’ve got to go all the way back to the founding of Baltimore.

Baltimore Town was founded in 1729 and it was small. It was even less acreage than what we think of as downtown proper today. There weren’t a whole hell of a lot of people or any neighborhoods- just about two churches and a handful of incredibly rich families who’d been given a shitload of land by the king of England. (After all, Baltimore was not in the United States at the time- it was part of an English colony.) The town was situated in the midst of a handful of other incredibly rich people who’d been given land nearby; the Carroll family, John Eager Howard, The Joneses, Admiral Fell, Charles Gorsuch, the Garretts, etc. Then as now, the rich had a tendency to get richer. If they could have kept to themselves in their mansions and estates that would have been just fine with them. But goddamn it fields won’t plow themselves and ships won’t unload themselves and factories won’t make widgets all on their own.

The rich needed labor.

So Baltimore Town began to fill up with Germans and Irish and Italians and Polish and a bunch of other people who weren’t Noble English. Back then it wasn’t a question of which neighborhood you wanted to live in, but which town offered work. Baltimore, the Port of Baltimore, Fell’s Point, etc were all separate towns.

Fast forward to after the Revolution and the beginning of Industrialization. Without the largesse of king and Nobility to lean on the city’s Elite decided it was time to stop fucking around and really get rich. Business was booming around the waterfront from Canton to Locust Point, and the Garretts had decided to build the B & O railroad, industrializing Pigtown. These areas started filling up with working people living in what we’d think of today as slum conditions- tarpaper shacks and the like. The Rich were loathe to live among the people and started marching up Charles Street, outside the city to what is now Mount Vernon. Using their great fortunes they constructed a monument to General Washington and encircled it with mansions and cultural institutions like the Peabody conservatory, Pratt Library, Walters Museum, etc. Ostensibly these were great Democratic institutions for the benefit of the city but come on… how many shipyard workers were slathering tar on hulls all day and then walking from Locust Point to Mount Vernon? Not too fucking many we’d wager.

As the rich and Elite were fleeing the rabble, poor people were sorting themselves out. Germans stayed downtown and in Otterbein, Italians built a church and a neighborhood around it. Polish did the same in Fell’s Point, Jews stuck together around the current location of the Jewish Museum, Irish, Eastern Europeans and the rest all did likewise. At this point blacks fit between the cracks not living in proper neighborhoods. Slavery was still going strong.

There was an incredibly disjointed system of surveying and subdividing land and developing blocks a few at a time. (Although the rich never really did part with their land and even today the city is straddled with a completely fucked up system of ground rent in which homeowners pay rents to massively rich investors for the ground their house sits on. Many of these institutional investors are foundations who trace their roots to the city’s great plutocratic fortunes going back to the Gilded Age and beyond.) Years pass. Slavery and the Civil War end. Jim Crow neighborhoods form in earnest around what is today Old Town and Druid Hill Ave. Manufacturing starts to boom. The city continues to annex territory and the rich continue to expand into areas like Old Goucher and Bolton Hill while the poor stretch out east to west.

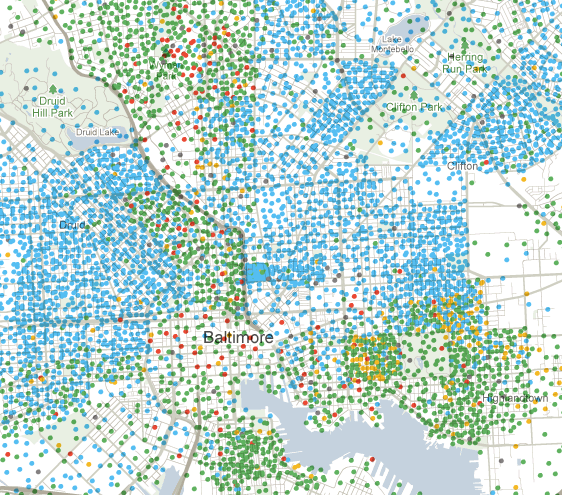

It’s at this point, some time in the decades before 1900 when the Civil War has caused mass migration that we’ve got to really start dealing with race and segregation. From here on out, blacks and whites are not going to live together in Baltimore. Here is a US census map describing racial lines in present day Baltimore. Green Dots are white people and blue dots are African Americans.

The contrast has been no less stark at any time in the last 130 years. It’s around 1870 that what we’ve come to think of as some of our most “charming” and ‘historic’ neighborhoods are beginning to take on what’s more or less their current form. This is about when many surviving rowhouses in Fell’s Point and South Baltimore are being built. The Great Fire happens in 1904 and Downtown is entirely rebuilt from the ground up. Mills are open several miles up the Jones Falls and new towns like Remington, Hampden and Mount Washington are being built around them. Villages are sprouting along dirt roads that lead to Pennsylvania along what’s now Greenmount Ave and Park Heights Ave. Although it’s bigger than it’s ever been, the city is still relatively small. People live in houses that allow them to walk to work, whether they work in a shipyard, brewery, factory or law office.

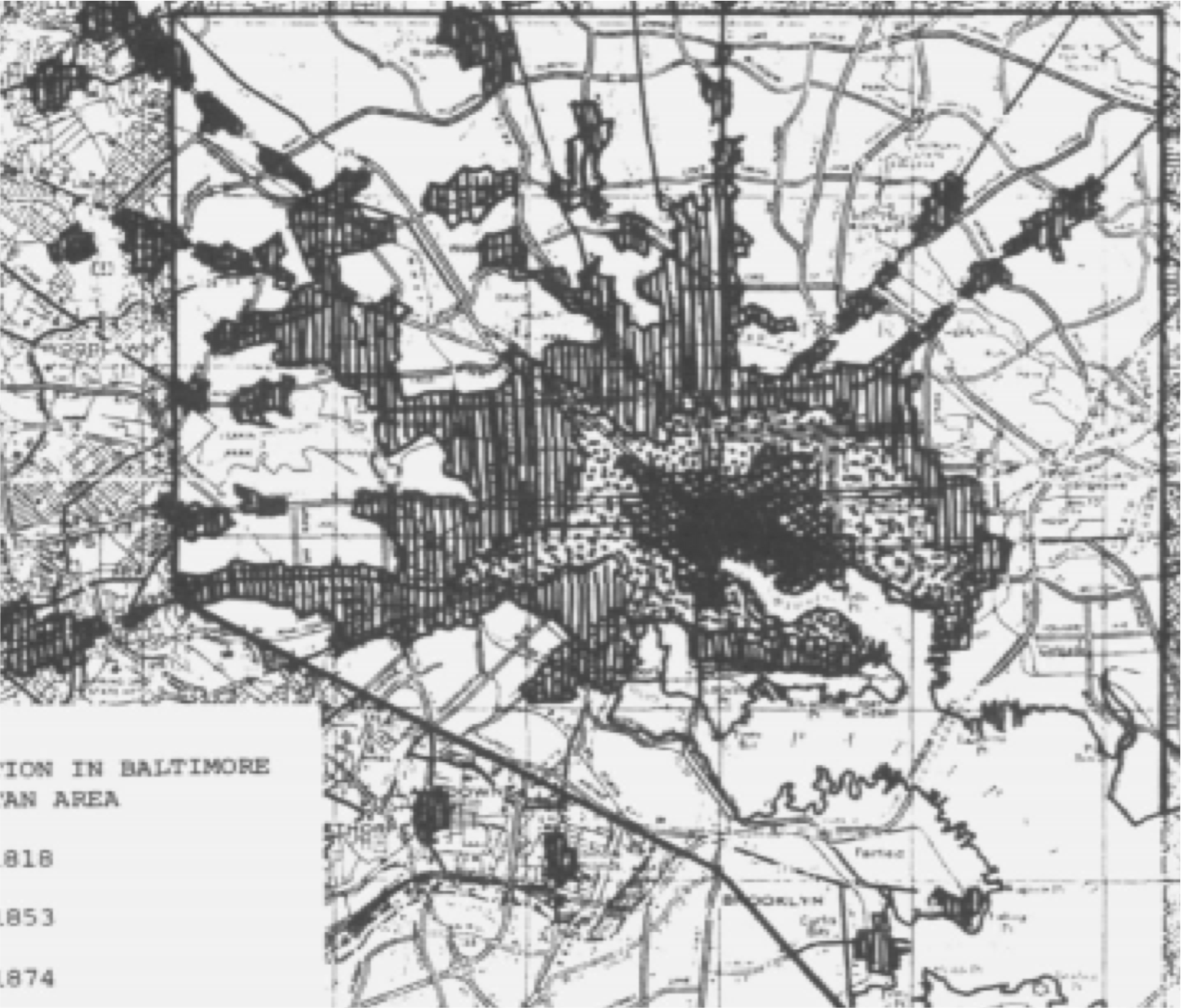

It’s just after the time of the fire’s reconstruction that two revolutionary changes allow people to live further than a mile or two from their jobs, and enables new neighborhoods to be developed on a large scale. The first is the perfection of Baltimore’s streetcar lines. These lines had been in place for some years, but at this time private companies were competing to run very efficient all-rail routes with the only other traffic in the streets being horses and carts. For the first half of the 20th century Baltimore’s development went hand in glove with its streetcar system. The second revolutionary change was the invention of the Model T, which had as much impact on Baltimore as it did on every American city and allowed the first real suburbanization to begin in earnest. When we went Googling for maps, right before we began typing the sentence you’re reading right now, it didn’t take us long to find this page in which a Hopkins student surprises himself by learning what most natives already know: that streetcars formed the city and that suburbanization began earlier and closer to downtown than most people imagine. (Incidentally, arcane streetcar lines form the basis for our current mass transit system which is a big part of the reason why the entire bus system is confusing and dysfunctional.) Here is what Baltimore looked like as it developed between 1818 and 1918: (credit)

1918 Was also the year that Baltimore undertook its final expansion to where its current borders lie. Like most cities in the country though, it was expanding with an eye toward further growth and suburbanization and the outer areas of the map of Baltimore were still largely empty farms and green space. Why do you think they decided to build Pimlico where they did (in 1870)? Because the area was full of horse farms, of course. Even today when traveling through Northeast and Northwest Baltimore a sharp eye can pick out a 150 year old farmhouse tucked into a much newer neighborhood. There’s one at the end of our block as a matter of fact.

There are some other important things happening right around the end of the First World War that we have to mention here. The rich and professional classes continued their creep northward, and the Roland Park Company had by now recently developed brand new neighborhoods around Roland Park and Guilford, which are significant nationally as some of the first planned suburbs in the country. At the same time production was near all-time highs in the steel mill at Sparrows Point, thanks in part to the war effort. Bethlehem Steel formed a company to copycat the development that was taking place in Roland Park in a more democratic form in Dundalk. Old Dundalk was then developed as a company town among farmlands.

The 1910’s is also when the Chop’s own grandparents were growing up as kids in downtown Baltimore. Our great-grandparents on both sides were part of this first wave of suburbanization, with one set moving from Saratoga Street downtown to a brand new house in the great wide expanse of… West Lanvale Street. The other set went from S. Castle St. to Old Dundalk, close to work at Sparrows Point. But as a recent City Paper story points out, even our earliest suburbs and company towns were segregated by race and remain so today. By the time our grandparents were coming of age Baltimore’s working class neighborhoods from Carroll Park to Highlandtown and across the water to the south had long developed their own character.

At this point neighborhoods are becoming truly inter-generational. In the rowhouse neighborhoods of East, West and South Baltimore adult children are buying houses near their families and near the friends they’ve grown up with all their lives. Your neighbors aren’t just your neighbors; they’re your cousins and co-workers and fellow parishioners at church. People throughout the 20th century would inherit rowhouses after deaths and see them not as an asset to be liquidated but a family home to be kept in the family. When we talk about a ‘close-knit’ neighborhood, this is what ‘close-knit’ really means. It’s more than just organizing a block party or helping your neighbor shovel snow: it takes generations to accomplish. Courtney Speed, the community leader in the City Paper story, has lived in Turner Station for fifty years.

None of our blue-collar neighborhoods would have ever inspired this kind of generational loyalty if it weren’t for two simple yet abstract concepts that apply equally to black and white and are all but completely vanished from the inner-city today: Catching On and Making Good.

In a close-knit neighborhood in the 20th century there was no Linked-In and no networking events. There weren’t even resumes. Anyone who wanted a job didn’t have to go any further than the corner bar (or Speed’s barber shop) to hear about who was hiring. Once you heard it was just a matter of going down to the Point or Crown Cork and Seal or CSX and getting hired on.

Now, wherever you ended up you might not like it- so you’d go on to the next one until eventually you find a job that suits you and you catch on. Once you’ve caught on you put in your time and pay your dues and eventually you make good by improving your skills and moving up the ladder a bit. For new generations of workers at this time access to jobs was not directly dictating where they lived, but it was certainly a major factor in the decision.

Here we reach a paradox. Among today’s urban planners and civic-minded intellectuals and even Progressive city residents there is fairly widespread support for the neighborhood-as-a-village model of revitalization and marketing. Many would like to try to re-create the ‘close-knit’ feel of yesteryear. But whether it’s the dockside heritage of Fell’s Point or the pride and history of Pennsylvania Avenue, you don’t arrive at ‘close-knit’ without a lot of racial prejudice and quite a bit of class delineation.

Housing issues in Baltimore have always been overtly racist. Let’s repeat that for emphasis: Racist with a capital R. Here’s a few examples off the top of our head:

-

The physical barriers that even today stop traffic along streets like Greenmount and Fairmount Avenues. For miles at a stretch large curbs and planters and other artificial impediments block motor traffic and separate black neighborhoods from white ones.

The construction of High-Rise public housing towers.

The displacement of black neighborhoods along route 40 in West Baltimore for highway construction.

The generation-long systematic practice of Block-busting undertaken by developers and Realtors about which books have been written.

And last but not least the widespread practice of banks and mortgage lenders secretly “redlining” the city according to race and refusing to issue mortgages or other loans to entire swaths of the city based on race and class.

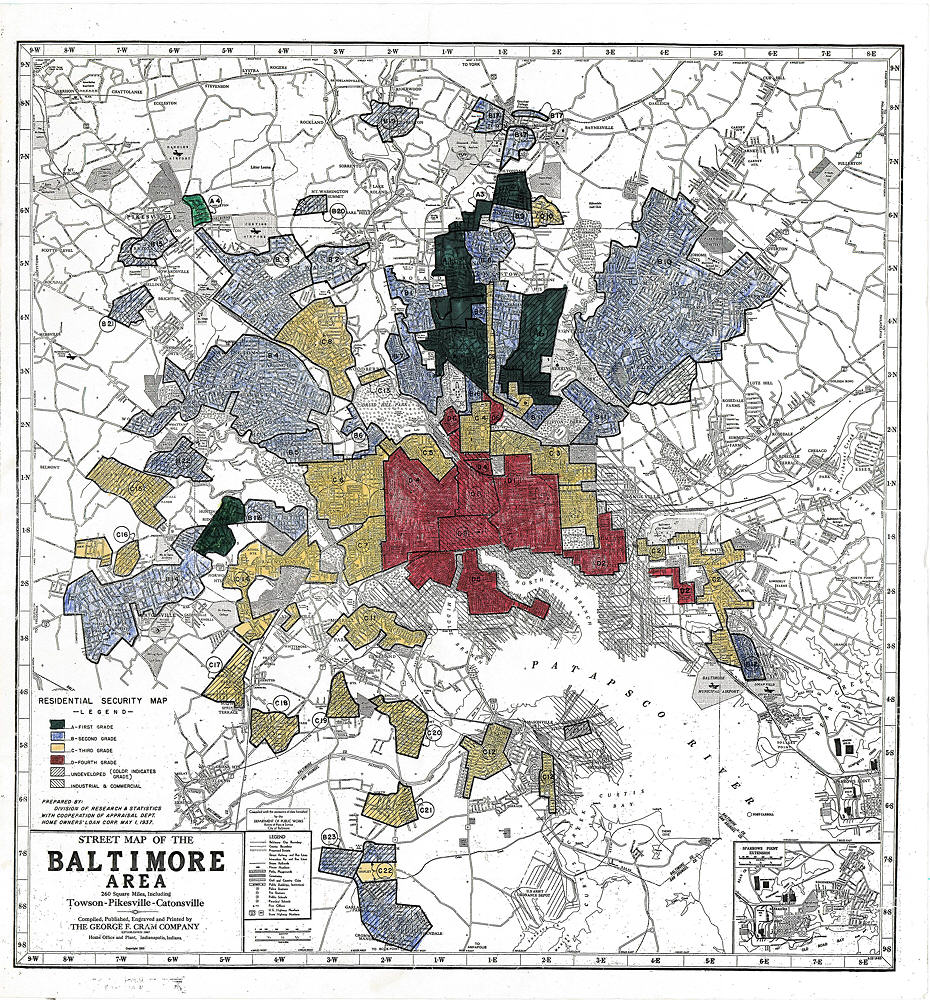

The Baltimore Brew has an interesting review of one of the books mentioned above that discusses block-busting and red-lining in more detail. Below is a 1937 map from that post showing how a mortgage company delineated neighborhoods for the purpose of loan making. It provides many interesting comparisons and contrasts to the census map above. For example, Greenmount Avenue is still a stark dividing line, but waterfront neighborhoods have completely transformed. Any bank today would be glad to lend money to build a roof deck on a Canton rowhouse.

To suggest that the city is not still affected dramatically by all of this and more over our very long history is either naive, disingenuous, or both. If there’s a silver lining it’s that today’s planners and intellectuals and residents at least value the idea of diversity more than ever and are willing to try to reconcile it in a way our parents’ generation never did.

Speaking of our parents’ generation let’s talk about the Baby-Boomers. Specifically let’s talk about the Chop’s own parents and aunts and uncles. Every one of them Caught On somewhere, and all of them Made Good eventually, with most of them buying their own houses around Dundalk. But they were the first generation who’d truly grown up with cars. Eisenhower came along in the 50’s and built 95, 83, 97 and 695. Fast forward again to 1993 and NAFTA. Our whole family had Made Good, but there was no one coming up behind them. Sparrows Point had hit the skids and would never recover. Every industrial concern that was employing Neighborhood Folks was right behind it. Downtown industrial buildings were being demolished and stadiums were taking their place. Houses in south and southeast Baltimore start falling one at a time into the hands of landlords and speculators.

Boomers were the first generation who ever accepted a car commute as a fact of life. For them and their White Flight mentality a 90 minute commute each day was perfectly acceptable. Our own parents couldn’t wait to ditch a house at the edge of the city for a newer house and a bigger yard, and landowners and developers were happy to oblige them. By the time we moved to Bel Air in the mid 90’s we found very few kids at school who were born in Harford County. A typical lunch table in the cafeteria might have had one kid from Bel Air, two kids from Dundalk, one from Essex, one from Rosedale and one from Fullerton. Of course, we all thought the Suburbs were terribly boring and couldn’t wait to get the hell out of there.

And Bel Air was boring in 1995. Even then most of Baltimore’s outer suburbs from Harford to Hunt Valley to Carroll County hadn’t been built yet. Their growth would be exponential from that point on and last until the housing crash of 2007.

By 2007 your Chop has Caught On somewhere and has been renting houses around the city, finding we had to move uptown after being priced out of one of the smallest houses on one of the narrowest streets in Fell’s Point. We’re starting to think about buying a house of our own. When you go to sea and have no kids there’s no commute and no concern for school districts, so two of the main reasons why people live where they do didn’t apply to us. We might have gone back to Dundalk Ave, but why? There’s nothing left there for us anymore. We would have liked to move anywhere between Fell’s Point and Bayview, but we’re pretty much priced out of that part of the city we’ve always known and loved. So we cast a wide net. We drove by thousands of houses, and toured dozens of them from Pigtown to Greektown to Remington to New Northwood always constrained by price, wanting to be at least somewhat central and not too far into the margins of drug and gang territory. In the end we bought in Waverly. Every house that made our buying short list was in a marginal neighborhood. If we hadn’t ended up here we would have ended up in Remington or somewhere along East Baltimore Street.

Buying here was an intensely personal and incredibly important decision, but also one that was practically made for us by 300 years of history, which is of no consequence because we’ll probably move sometime after getting married anyway. We’re committed to living in Baltimore, but we’ve got no reason at all to commit to any particular neighborhood beyond a fleeting affinity for it.

We’re certainly not alone in that. For our own generation and especially anyone younger than us it’s difficult to commit to one city for life, let alone a neighborhood. For anyone under 40 moving to the city from outside, gentrification isn’t an aberration, it’s the expectation.

What makes one neighborhood more ripe for gentrification than another? Water views? Sure, that doesn’t hurt.

But let’s be honest here- so far it’s only historically white neighborhoods that developers have seen fit to gentrify. It’s why the gentrification of Federal Hill spread south to Riverside but not west to Sharp-Leadenhall. It’s why the gentrification of Canton is poised to reach into Greektown but never made it more than one block north of Patterson Park. It’s why small businesses are falling all over themselves to open in Hampden but Belvedere Square is continually a work in progress. It’s why Bolton Hill is an impressive historic neighborhood and Marble Hall is a collection of dangerous abandoned buildings. It’s why young families flock to Lauraville and not to Bel-Air Edison. It’s why everyone rides the light rail and no one rides the subway.

To choose a neighborhood in Baltimore first means to choose across race lines. Then to choose across class lines. Then to pretend that choosing a neighborhood is as easy as choosing between Doc Martens and Top Siders and that race and class have fuck all to do with it. That is what we find so distasteful in the Sun’s quiz.

It’s the same thing that many Baltimoreans found extremely distasteful about a certain rant on Medium a few months ago. Yes. We’re going to beat that very dead horse some more. We don’t have anything against Tracey Halvorsen personally and we’d bet she’s probably a pretty nice person in real life, but that post was just Godawful.

It sounded the dog-whistle tone of race louder than most things that ever see the light of day on any website. The only person who doesn’t want to admit that it has racial overtones is its author. Much has been made of that post since, but it’s worth addressing here because even though it reads as a rant about crime it is essentially the personal epiphany of a gentrifier without a deep connection to her city or her neighborhood.

Approaching middle age, Halvorsen says she now realizes that the place she lives is more the result of circumstance than of deliberate choice, and her circumstances are pretty favorable. Let’s have a look at what we imagine those circumstances might have looked like: come to Maryland from outside after college to get a graduate degree at a ridiculously expensive art college. Live near MICA during and for some time after grad school, probably in Mount Vernon or Bolton Hill. Get a job, get a better job. Look toward being president of a company. Decide it’s time to invest in a house.

If we work backwards we can determine how Halvorsen wound up in Butcher’s Hill. Her office is near downtown and she didn’t want to be a commuter. She probably wanted a house of a certain size, with a bit of yard space for a dog so much of Fell’s, Canton, and South Baltimore was ruled out. They would have been ruled out also because people over 30 often don’t want to live too close to the bars. However, she has got expensive taste in restaurants and doesn’t want to be too far from her favorites. It’s also likely she sees herself as someone who values the idea of diversity, and wanted some sort of historical character in her house. A late edit in the post reveals she’s looking for that ‘close-knit’ that doesn’t really exist anymore and gives her idea of the ideal neighborhood:

“clean and litter free, people outside talking, neighbors saying hello to each other, homes and sidewalks that look cared for, and people who want to know you, engage with you, and care about the neighborhood. That doesn’t mean affluent, white, or privileged — to me. And if you were to really know Butcher’s Hill, you would know it’s full of all kinds of people with different income levels, backgrounds and opinions.”

Now for a large house with park access about 20 minutes or less to downtown she could have bought a house on Union Square, or in Reservoir Hill or somewhere along Parkside Drive or Gwynn’s Falls Parkway or even in Ednor Gardens Lakeside. But that was never going to happen. There was 0% chance of that ever happening. It was preordained that when Halvorsen bought her first house it would either be in Butcher’s Hill, Barre Circle/Otterbein or Little Italy. Not all strictly white neighborhoods, but all white enough. She chose to buy first within race lines, then within class lines as most people do, even then in a very particular type of neighborhood- one with a certain sort of cachet. We do know Butcher’s Hill, and we know that ‘diverse’ isn’t really the mot juste for it. Marginal might be a better choice. For someone who claims to love Baltimore’s history, we get the distinct impression that Halvorsen hasn’t dug into it very deeply.

So Tracey Halvorsen bought into a marginal neighborhood and is now running right up against some very uncomfortable feelings. Fine. But something that affected many readers the beyond the dog-whistle tone of her post was the whiny and entitled nature of it. It’s as if everyone in city hall should answer to her personally. As if all city residents should count our blessings to have someone as concerned and educated and neighborly as Halvorsen living in our midst. Because if she leaves and takes all of the TEDx Talk set with her and fucks off into the mountains in an Atlas Shrugged style form of protest we’d all be fucked and the city would collapse in no time.

Balls.

We say go ahead, Tracey. There’s the door. When you leave you’ll want top dollar for your house, and the person who buys it will be not terribly different from you. Probably working at Hopkins with an advanced degree of their own and on the young side of middle age. Make your home wherever you see fit, but do it as a personal choice and not as a political statement. The lines of race and class have been in place for a long time now and no amount of hand wringing on Medium is going to change them. We’re sorry your neighborhood wasn’t everything you hoped it would be but nobody gets to live on Sesame Street. If it makes you feel any better there’s plenty of violence up here in our marginal neighborhood, too.

Now that that’s off our chest, let’s say something that hasn’t been said yet in the big blustery reaction to Halvorsen’s post. Perhaps the thing in it that caused the most angst and anxiety in the hearts of well meaning liberals is the fact that there but for the grace of God go us. Sure, few of us can fit our foot that far into our mouth, but for ‘middle class’ people of all races who choose to call the city home we do it by dint of what is a mostly superficial choice. We do it because we like nice restaurants, too. Or we live here because we don’t want to commute or for whatever reason. Without that base of blue collar jobs the city is just another type of county. Deep down a lot of us don’t want to admit that we’re all Looking Out For Number One and that a commitment to the city that we feel is deep could be dredged to the surface pretty easily. An attractive job offer or a four year old who needs to start kindergarten or a close call with violent crime or a raise in rent could push anyone out of their neighborhood or out of the city quickly, and you can’t really blame them for going. For our generation, none of us have roots as deep as Courtney Speed, and few of us ever will.

At the founding of Baltimore the Elite controlled the waterfront and used it to bring in Big Money, creating jobs along the way. The rest of us fit in as best we could. The Elite still control the waterfront, but now instead of making Big Money on steel and shipping and canning they’re making Big Money on Condos in Locust Point, Hotels in Harbor East, and suburban style big box sprawl in Canton. Those who can afford it buy into a fantasy lifestyle, and the rest of us get in where we fit in, same as ever.

So what will change those lines? At the end of the day how do we organize city neighborhoods across racial lines for the good of all? It seems to us that the first step is admitting those lines are real, and that they are as old as the city itself. Preferable to organizing across them would be finally wiping them out once and for all.

How do we do that? Gee, we wish we knew. We’d be happy to tell you.

A good start might be ending predatory practices like sub-prime mortgages and payday lending and insuring credit is available wherever it’s worthy. Creating a critical mass of living wage blue collar jobs and job training options would help as well. In the days of Catching On and Making Good employers invested in their own employees. Now even the most basic entry level job often requires applicants to have invested heavily in their own training, either through colleges or other learning institutions. Oh and if we could find a few billion to invest in the school system that wouldn’t hurt either. Unfortunately erasing the lines isn’t as easy as simply crumpling up the map.

In any particular organizing case or campaign; from the Red Line to the cargo-rail terminal at Morrell Park to Harbor Point to the EBDI project and beyond, it’s important to make people understand that what’s in their own narrow personal interest isn’t necessarily what’s best for the city. Likewise what’s in the interest of the area’s modern plutocrats like Peter Angelos, The Rouse Company, Michael Beatty and John Paterakis. Often neighborhood issues are in fact citywide issues, but city residents will never speak with one voice. It’s hard to push back against the forces of history, and impossible if we don’t know what those forces are. Our neighborhoods didn’t fall from the sky fully formed exactly as they are today. We are all here by circumstance. Whether a person’s circumstance has allowed them to choose a luxury waterfront condo, a rowhouse in SoWeBo, a mansion in Roland Park or whether it’s left them little choice at all that person will continue to act in their own self-interest first. Even if it ‘breaks their heart.’